In the second of our succession series, Richard Hartung looks at succession from an Asian perspective. This article was preceded by: ‘The succession swindle: Why advisors should do more to help the next-gen’

High net worth individuals and the mass affluent in Asia hold nearly US$40 trillion in assets, according to consulting firm PWC, and a significant portion of it will transfer from one generation to the next within the next decade or two.

In capturing this wealth, private banks in the region have a tremendous opportunity to grow their assets. However, they can also lose out if succession plans go wrong, or wealth transfer is left until it is too late.

Succession at Stake

One key issue for succession in Asia is a lack of planning: 57% of HNWIs in Asia have done nothing for estate planning and wealth transfer, according to BNP Paribas, compared to 32% in the West. A study by RBC also found that 60% of those without a wealth-transfer plan lack confidence in their children’s ability to grow or even just preserve their wealth.

While most HNWIs and UHNWIs in Asia have earned their riches through a family business, BNP Paribas said that almost two-thirds of business owners had not named a successor. And even though Asia’s wealthy recognise the importance of family financial planning, most fear that transferring their wealth will negatively affect the motivations of their beneficiaries and therefore avoid discussing legacy planning with their offspring.

Teddy Chu, BNP Paribas’ head of Wealth Planning Services for Asia, outlines two aspects of wealth planning: The transfer of ownership and transfer of power or control. Successful Asian businesses are mostly family-owned, he notes. The first generation has control and wants to remain in charge for as long as possible. The challenge is how to balance the transfer of wealth without them losing control.

While each country and each family is different, those views are common across Asia. Bank of Singapore managing director Terence Seow says the Asian model tends to focus on preserving wealth to provide a legacy for children and filial piety is deeply entrenched.

Seow also noted that there are significant differences between countries. In China, for example, the first generation tightly controls their business and often does not spend on themselves even though they have more than enough money. Instead, giving more is their way of showing affection to their children.

Indian families, on the other hand, are better at training children to take over the family business. But Singapore, Seow says many in the next generation want to build their own company rather than climb the corporate ladder of the family firm.

What the Next Gen want

What the Next Gen want

“The first generation is more old-fashioned, there is a different way of communicating,” says Chu. First generation HNWIs in Asia, he notes, often prefer to meet their private bankers in person, whether in well-appointed offices at the bank or on the golf course and tend to prefer traditional assets such as real estate or equities. Seow says they are often practical people with practical ideas.

The younger generation in Asia are often given the opportunity to study abroad, Seow observes. On managing the family’s wealth, most of them think they know how to manage wealth better than their parents. However, these academic scores have not been tested. Additionally, they prefer to do their own business or to start up a new venture with their own networks and connections rather than to start from bottom up in their father’s organisation or to join a large international corporate.

One of their goals is to invest sustainably and they often tell their parents to look at more sustainable investments, says Standard Chartered Bank head of sustainable/impact investing Eugenia Koh. “We work to help with conversations,” she says.

This digitally-savvy sustainability-focused younger generation also prefers different types of wealth advisors, ones who are comfortable communicating digitally and who are ready to talk about tech trends or green investments as well as private equity or impact investing.

Succession strategies that work

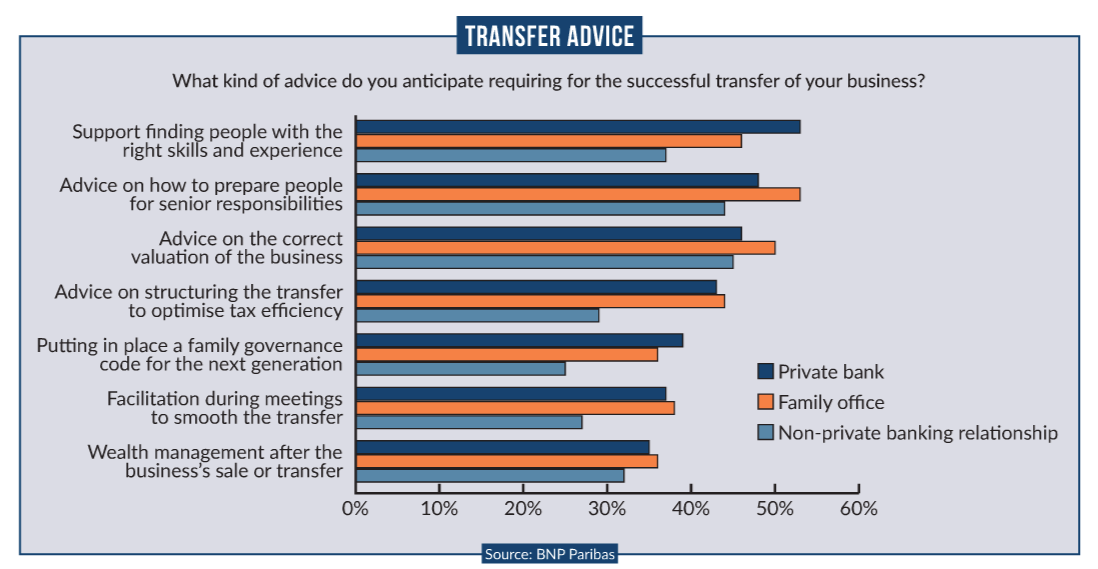

Fortunately, most HNWIs and UHNWIs realise that they may need some advice. In a survey by Singapore Management University and the Family Business Institute of 290 family businesses across Asia, 39% said they need good advice on succession planning and 40% said they need advice on corporate or family governance, while only 10% needed advice on investments.

Chu says relationship managers often team up with wealth planners or other professionals such as lawyers or accountants to come up with the right structure: “We will identify in-house or external solution providers such as independent trust company in order to meet clients’ needs.”

Bank of Singapore leverages wealth planners to help with asset structuring and trusts, according to Seow. “We as bankers share experience based on what we know about the family background, relationships between parents and children, and value systems they have.”

Many families set up trusts, Chu observes. This allows the first generation to transfer the ownership to the next generations but retain control and the second generation can be involved in decision-making processes, leaving them to take over eventually.

Whereas Europeans and Americans may transfer control of a family’s wealth to a capable outsider, in Asia it is usually transferred to the eldest son. And while Asia is catching up, Europeans and Americans often have more a philanthropic element to their planning.

Bankers also take different family backgrounds into account, Seow said, as different cultures have different styles. Some are more guarded, while others let their children take risks. “We are good listeners, trying to find the best solutions.”

The Three Trends

As they work to deliver advice and support wealth transfer, three trends at private banks in Asia stand out.

First, they are increasingly leveraging technology to serve clients better. Capgemini, a consultancy, observes a gap between demands for technology-empowered advisory services and what private banks are able to offer. Leading private banks in Asia such as Credit Suisse and DBS are developing facilities for secure videoconferences, and offering aggregated digitally-delivered portfolio insights. All of these help to maintain contact with the next generation.

Next, some private banks are partnering with companies outside of their industry. Partners can provide expertise in areas popular with the next generation such as art, culture, sustainability or lifestyle. Standard Chartered in Singapore, for example, partners with Blackrock and Allianz for sustainable investments and uses a third party to assess companies’ ESG compliance.

Finally, private bankers are becoming educators. Multi-day or week-long next generation programmes run by private banks in Asia have become commonplace, with added events during the year. “We provide training for the second generation about what is available and suitable”, says Seow. While these programmes do not directly generate revenue, they have become an integral feature of a comprehensive service offering and help to cement relationships with the younger generation of clients, who might not otherwise remain loyal to their parents’ bankers.