Over a decade of ultra-low interest rates has been a boon for the Private Equity (PE) industry. The sector has approximately quadrupled in size since 2010 (AUM basis), as investors shifted allocation away from the mainstay asset classes in search of better returns. Cheap borrowing uplifted asset prices across the board, but it also turbocharged the leveraged buy-out (LBO) model at the core of the PE industry. Yassir Ahmed writes

Higher (and cheaper) leverage and expanding exit multiples drove momentum on asset valuations and transaction volume, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of increased returns and further investor interest.

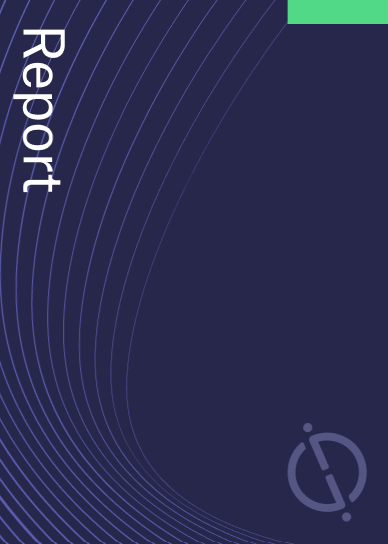

Fast forward to today and the deal-making music has slowed dramatically. Central banks have been compelled to raise interest rates much faster and higher than anticipated, and as inflationary pressures remain, are wary of lowering them too soon – “higher for longer” is quickly becoming a reality. Against this backdrop, PE’s investor proposition has become relatively less appealing, due to higher opportunity cost for capital ‘locked’ into PE funds and greater uncertainty around achievable returns. Asset valuations are yet to fully re-rate to a higher cost of capital environment and the IPO market remains subdued, raising concerns around PE’s ability to successfully exit investments. The indirect PE investment proposition is not faring as well either, as the average return of publicly listed PE firms and the risk-free rate continues to converge (see Figure 1).

Unsurprisingly, investors are now recalibrating their exposure to the PE sector, increasing pressure on PE firms to return capital in a market environment where successful asset exits are hard. The initial response has been to delay exits and wait for better market conditions (median PE asset holding times have now reached a 10 year high).

However, some PE funds will be compelled to sell assets as funds approach end-of-term, investors request early redemptions (where allowed), and/or debt-servicing costs become unmanageable.

A solution the sector is increasingly resorting to are continuation funds; where assets are sold to a new fund owned by the same PE (usually with new investors and more favourable terms). This has not been without controversy however, with some commentators likening continuation funds to a “Ponzi scheme”. Alternatively, PE firms have been borrowing more to fund distributions to investors, often through more exotic debt instruments (e.g., private credit, NAV loans) and typically with less stringent covenants and much higher rates of interest.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThese tactics cannot be relied upon indefinitely and highlight the strain the PE sector is facing more broadly. Thus, PE firms will invariably need to start selling assets at lower valuations, and this opens up opportunities for strategic acquirers – i.e., those not dependent on high-leverage for deals, have a longer investment horizon, and/or can quickly unlock synergies with their existing portfolios. With reduced competition from other PE firms for the foreseeable future, strategic players have an opportunity to buy quality assets at more reasonable, if not favourable, valuations.

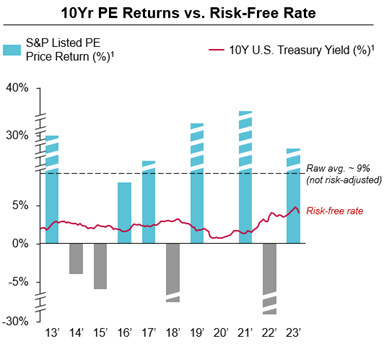

Fewer and larger strategic acquisitions targeting PE portfolios is likely to be the forward trend, and empirically, this is already starting to happen. In 2023, the deal count on PE exits to corporates reached a 10 year low, but average transaction value reached a 10yr high (except for 2018-19, where four ‘mega-deals’ skewed the trend) – see Figure 2. Notable strategic transactions last year include CVS’s $10bn acquisition of Oak Street Health (to accelerate CVS’s expansion in primary care clinics) and Merck’s $10bn acquisition of Prometheus Biosciences (providing portfolio diversification for Merck via a foothold position in the fast-growing field of immunology).

There is a clear opportunistic play emerging, but pursuing it requires moving fast. Vulnerable high-quality assets are more than likely already on the radar of experienced M&A teams. Speed may be a challenge for some, as finding the intersection between the ‘right target’ and a potential ‘good deal’ is not straightforward in the vast and opaque landscape of PE portfolios. More fundamentally, there may be a lack of internal alignment around investing in M&A in a weak market environment. Hence, getting agreement on the “shopping list” and testing the waters with asset owners quickly is key (in our experience the best target assets usually need to be unlocked through direct engagement with owners, they are rarely the ones being shopped around between buyers).

Longer-term, there is a natural endpoint to this play, as inflationary pressures will eventually subside and thus interest rates will fall, enabling the PE sector to raise capital and maintain leverage more sustainably. While the PE industry is unlikely to return to the ‘boom times’ of the zero-interest rate era anytime soon, it’s likely the new equilibrium will result in more bullish asset valuations than today, as competition returns between strategic buyers and PE firms.

Stepping back, the outlook on the market environment remains generally weak, and in these circumstances the traditional response is prudence and patience. However, there may be material prizes for well capitalised players that are willing to get on the front foot and shake a few trees.

Yassir Ahmed is principal at Marakon