No longer are HNWIs limited to charity when wanting to give back, says James Badcock, partner and head of Private Client Services at Collyer Bristow LLP. However, their advisors need to keep up with the rise of donor-advised funds.

Earlier this year an opinion piece in the Times was provocatively entitled “When the rich stop giving they start to rot”, citing recent research that there is a dearth of charitable giving among the UK resident HNWIs, and arguing that today’s super-rich will be unfulfilled, will see their family’s fortunes squandered and will not leave the legacy of the legendary philanthropists of the past.

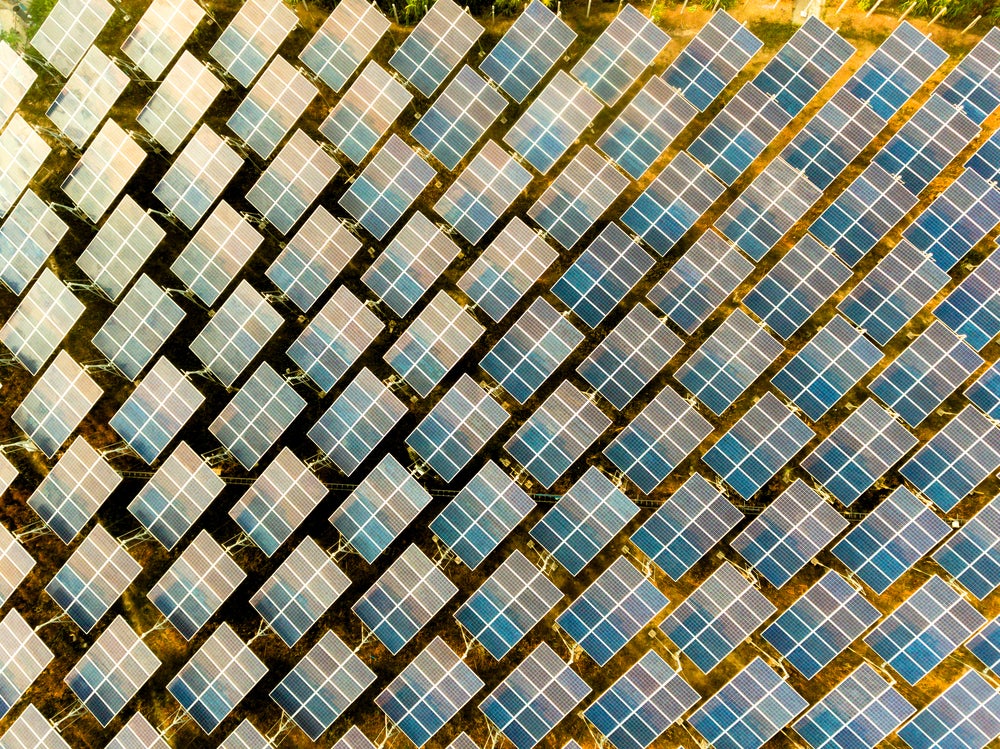

In answer to this, those standing accused might point to another trend, which is the huge growth in impact investing. This is investing with a view to a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return. Even before the charity sector was hit by high profile scandals, critics would point to a lack of accountability and transparency and the spending of funds on administrative costs.

Those who had made their money with sharp commercial acumen and financial discipline wished to practice philanthropy in the same way. Charitable foundations increasingly adopt the language of venture capital funds and angel investors.

Ultimately, the question of whether traditional charitable giving or impact investing are either more effective or morally superior than the other is a somewhat insidious debate and the reality is that there is not a binary choice but a spectrum of choices with greater or lesser emphasis on financial return. For clients who wish to give something back, there seems to be a bewildering array of choices, each involving complex moral and economic decisions.

For these purposes, the deployment of funds might be divided into three categories: tax, charity (which has a strict definition in English law and for tax purposes) and investment. Governments have permitted taxpayers a degree of leeway to choose to give to charity rather than the state. In other words, the taxpayer has a choice as to whether their income is divided between themselves and the state, or goes entirely to charity. Currently in the UK this is primarily dealt with through capital gains relief, the Gift Aid Scheme for income, and with inheritance tax exemptions and incentives for capital. Charities themselves do not pay tax on their income and gains.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataTraditionally the field of investment was quite separate from that of philanthropy. The main way in which ethical considerations impinged on investment decisions was through “negative screening”, by which businesses involved in activities which were undesirable in the eyes of the particular investor such as arms, tobacco, animal cruelty, gambling, pornography, nuclear power, genetic modification or fossil-fuels were excluded from investment portfolios. Of course, negative screening could have a positive impact, by financing “good” not “ill”. However the investor was not being particularly pro-active in deciding what was good.

Today the approach to ensuring investment portfolios have a positive impact has evolved into an entirely different beast, where investors actively look to invest in businesses which are having a positive impact with reference to environmental, social and governance factors (ESG). Financial institutions are deploying the resources necessary to construct such portfolios and help clients with these choices. More products are being developed and need to be developed for the growing demand from retail customers.

At the same time businesses are paying ever closer attention to corporate social responsibility in response to societal pressure, investor demands and national and international legislative and regulatory measures.

For the majority of clients, this will be the end of the story. They will give some money to charity and then gradually invest more of their retained funds in a way which has a positive impact according to their criteria. They will rely on professionals getting better at helping them to measure this impact. For wealthier clients the two might be combined, where money is given to a grant making charitable trust or donor advised fund, and then the trust or fund invests its capital in social impact investments.

For UHNW and some HNW clients a greater array of strategies is available both for philanthropy and impact investing, or in a space somewhere between the two. This includes investing in or providing finance to charities or social enterprises or to normal businesses which serve a positive ESG function. In the same way as with traditional charitable giving, the state is gradually adjusting to this innovation by providing tax incentives such as social investment tax relief and community investment tax relief.

There are also social impact bonds, products typically designed in conjunction with public bodies or private donors which provide a return for investors based on a measurable positive impact which reduces the need for public spending.

These strategies are still in a state of rapid development, and are subject to some controversy as to effectiveness, risk and investment return, which poses particular issues for institutional investors and trustees. However it is clear that investors have the bug, and advisors will need to become increasingly familiar with the impact investment landscape.