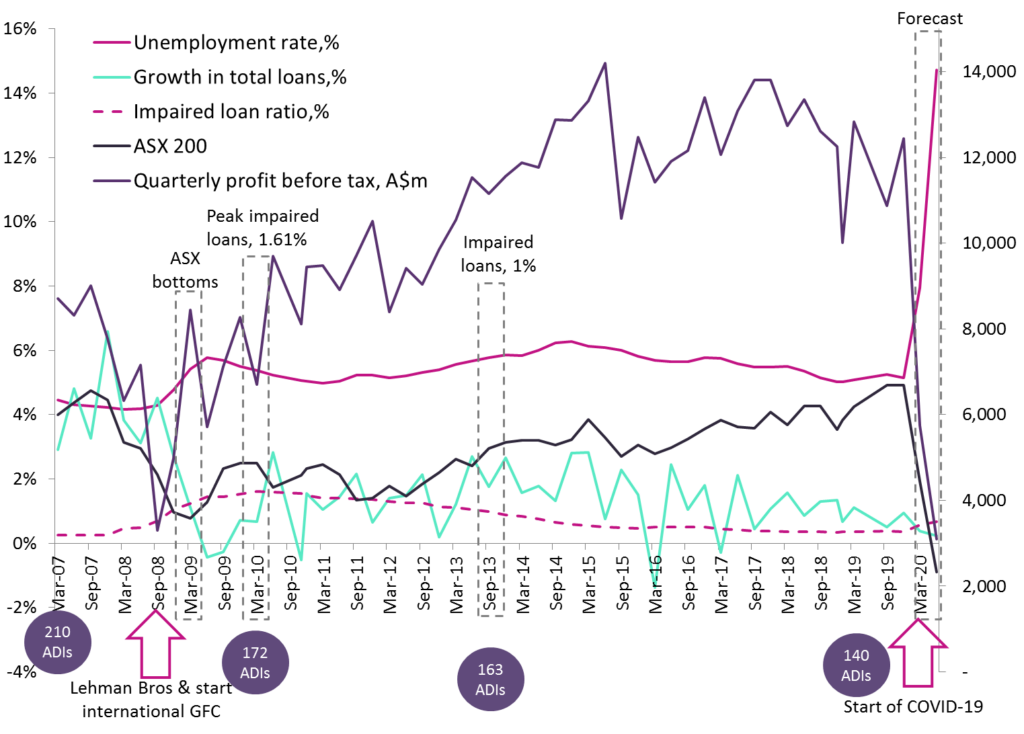

The medical effects of COVID-19 on Australia are still building, with caseloads rising and likely to continue doing so for some time. GlobalData examines the effects of the global financial crisis (GFC) for clues as to the impact on banks and the financial health of the nation, with implications not just for Australian banks but all mature banking markets facing down a COVID-19 recession. While still early days, indicators are that short-term bank profits will plummet, loan growths will stall, impaired loans will begin to rise, and the industry will see further consolidation.

The mounting direct medical toll is predicted to be grim and the measures needed to contain it are also shaping up to be devastating to the economy. Ever a leading indicator, the ASX 200 has cratered with the benchmark index well and truly in bear market territory – over 30% down as of writing. Large swaths of the service economy have been closed with unemployment numbers mounting to levels not seen in modern history. While not an ideal comparison, the banking sector’s experience with the last international crisis, the 2008 GFC, is the best guide.

Review of the GFC and predictions for the COVID-19 crisis

While a very different shock, there are lessons to be learned that suggest some short-term and long-term considerations for Australian banking:

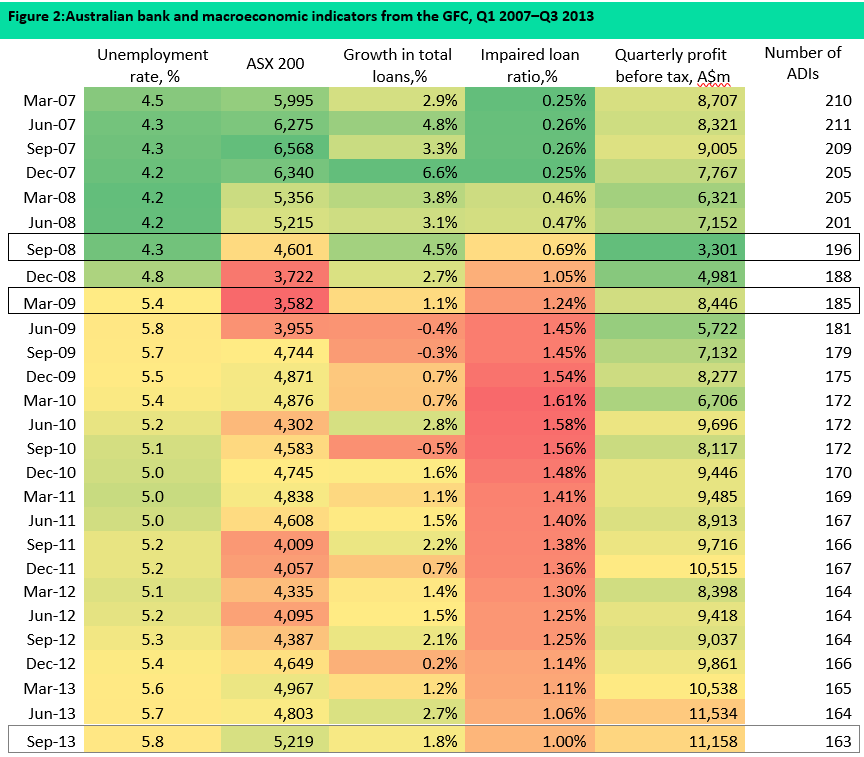

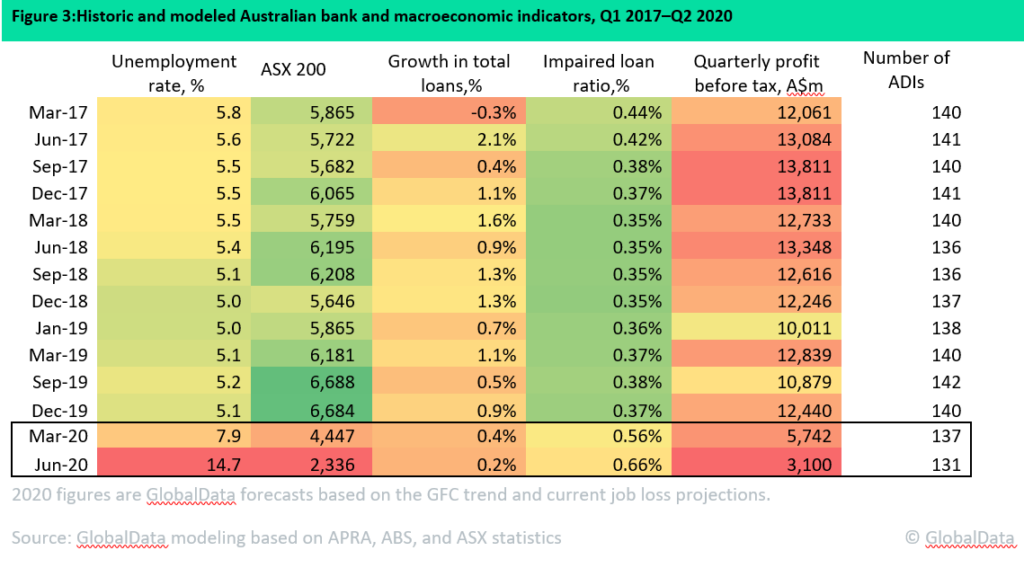

- First, share prices and the ASX are not likely hitting their bottom yet. The internationalisation of the financial crisis in September 2008, when it first became a clear and present danger to Australia, did not result in the bottoming out of the ASX until February 2009, five months later. It is highly unlikely that the ASX 200 will have seen its bottom in March from a crisis that only started in February; current modelling suggests that late Q3 is more probable.

- Unemployment also roughly peaked at 6% in early 2009 and remained elevated until Q1 2010, before beginning a downward trend with a more energised global economy. Here, the unemployment rate, even with government stimulus, is already predicted to be many times what it was previously, and it is suggested that only in Q2 can the true impact of COVID-19 on the economy be measured. Unemployment will be elevated for at least a year and will still need accommodation well into 2021.

- Following the financial crisis, total impaired loans did begin rising almost immediately but would not peak until March 2010 at a relatively modest 1.6%. Forbearance and financial hardship plans were rolled out then as they have been now, providing evidence that they do work, at least in the short term. Fundamentally, they aren’t the same as a regular income from a job and can only manage an increase in non-performing loans (NPL). Government efforts to provide temporary income to the millions thrown out of employment will work in the short term and hold down the impaired loan ratio for the first half of 2020, but pressure will be on lenders for many months following. It took years for the impaired loans ratio to creep back below 1% after the financial crisis; based on current timelines, this would mean banks are facing elevated levels of impaired loans until 2025 at the earliest.

- Loan growth will also suffer, despite efforts to keep lending to businesses and households at extremely attractive rates. The Reserve Bank of Australia and government funding to lenders will help, but it is highly uncertain whether there will be sufficient appetite for credit to see anything more than marginal increases in 2020. New residential mortgage lending will collapse during the weeks, possibly months, of lockdown and enforced social distancing as even viewing a property safely becomes a challenge. Spending, barring panic-buying, will decline and businesses will be hesitant to take on even attractive loans when they have no income.

- Finally, banks’ quarterly profits are expected to drop precipitously, most dramatically among the largest banks but with a more enduring squeeze on smaller authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADI) that results in the long-term consolidation of the market. Once again government support, particularly the cheap funding, will help but can only mitigate the impact. The recent upswing in ADIs, driven by the launch of neobanks, appears set to reverse. The next five years could see up to a quarter of ADIs exit the market via sales or mergers.

Given the expected scale and length of the disruption to the Australian economy, it’s no surprise that key banking indicators will suffer. The government stimulus measures for the banking sector and broader economy will limit the fallout, however, and at no time does it look like the banking sector will be pushed to the brink – even if profits suffer, there still will be profit. Even though NPLs will go up, it should be manageable given the government support. ADIs will suffer and not all will endure but it should be manageable.

What will be enduring is the effects that mass unemployment, possibly long-term, will have on lending and the increased use of automatic digital decisioning on loans. Large swaths of Australians are about to become non-standard risks and lenders are going to have to be able to roll with that for years to come – those that can adapt will be among the fewer lenders that we see in 2025. It is a tale that mature banking markets around the world will be telling as they endure their own version of the COVID-19 recession.

Figure 1: While faster moving than the GFC suggests, a collapse in bank profits, consolidation, and years of higher NPLs seem likely