A combination of political concerns twinned with the availability of foreign citizenships means that wealth is crossing European borders like never before. But that could all be about to end, Oliver Williams finds.

Private bankers frequently talk about wealth being more mobile than ever before.

The availability of ‘golden visas’ – citizenship or residency bought through investment – have allowed those with the means to hold multiple passports, while the globalisation of the finance industry means that money can cross international borders with ease.

As wealth has flowed between countries, so private banks and wealth managers have opened international outfits to accommodate the spread of wealth across Europe.

However, some are asking if this can last, given a series of scandals that have prompted regulators to look closer at the international flow of wealth.

The Individuals

Evidence shows that wealthy people often move country or apply for a second citizenship during periods of political or economic instability in their home countries.

Take Turkey. A crashing lira and political instability has caused around 4,000, or 10% of all HNWIs in the country, to leave Turkey in 2018, according to wealth researcher New World Wealth. According to its report, ‘Global Wealth Migration Review’, the next largest wealth movement as a percentage of HNWIs was Russia where 6% left the country.

Andrew Amoils, author of the report, told PBI people were leaving Turkey for Europe and the UAE. Turkey ranked sixth by number of applicants to the UK’s Tier 1 Investor Visa in 2018.

“Some years we see a sudden flow of migrants from countries we normally do not see Investor Visa applicants from, such as Iran, Turkey, or Brazil”, says Farzin Yazdi, head of Investor Visa at Shard Capital. “A few years later we hear and see those countries’ economies beginning to falter and other political uncertainties beginning to emerge.”

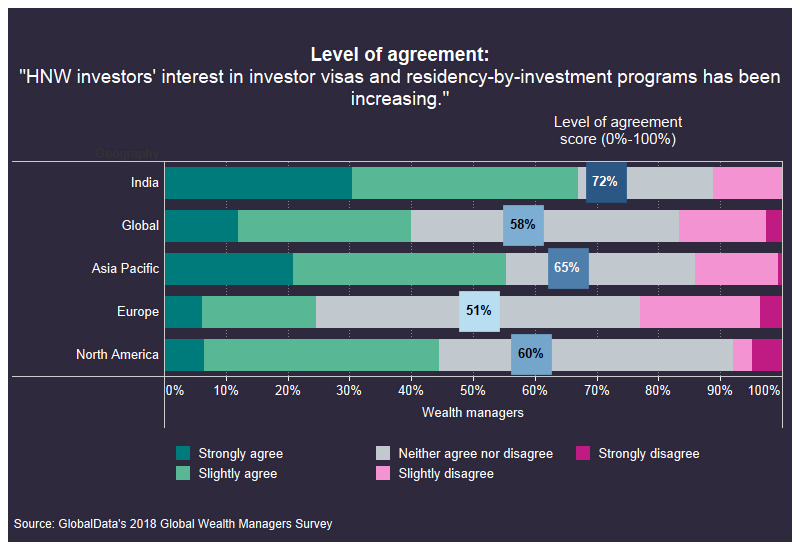

The same happened in India ahead of this year’s election. According to GlobalData’s ‘Wealth Management Industry Conditions Analytics’, 66.5% of industry participants “strongly” or “slightly” agree that demand for investor visas and residency-by-investment programs is on the rise among Indian HNW investors. Globally, this proportion drops to 40% (see table).

“Demand for investor visas and residency-by-investment programs is growing rapidly among Indian HNW investors,” says Heike van den Hövel, a senior analyst at GlobalData. (GlobalData is part of the same group as PBI).

According to a survey of applicants to the UK’s Tier 1 Visa by Shard Capital (“The last time anybody surveyed the investor visa space was in 2014”, says Yazdi), 60% were attracted to the scheme due to political uncertainty in their home markets.

The Banks

Ever since the sale of Coutts’s international arm – which had a presence in Switzerland, Monaco, UAE, Qatar, Singapore and Hong Kong – to UBP in 2015, there has been a steady flow of M&A activity among private banks’ overseas operations.

So far this year, Falcon Bank has sold its UK branch to Dolfin, Investec offloaded its Irish business to Brewin Dolphin and Vontobel brought Lombard Odier’s US private clients portfolio.

Others have announced plans to cut back: Julius Baer said it was pulling out of “non-core markets” after it missed profit targets at the end of 2018 and UBS is expected to make around 150 job cuts globally this year.

As well as the buying and selling of onshore operations, the same has been happening in the offshore markets.

A flurry of deals in April saw J Safra Sarasin buying Lombard Odier’s private banking operations in Gibraltar, N.T. Butterfield & Son acquiring ABN AMRO’s Channel Islands business and, in a local arrangement, Oak buying International Administration Group (IAG) in Guernsey.

The last few years have seen similar deal flows in other financial centres as private banks seek to re-focus their operations on core markets.

The Visas

Two other notable offshore moves have come from Deutsche and Danske Bank.

Authorities raided both banks this year, Danske over the flows of illicit Russian wealth through its Estonian branch and Deutsche due to dealings in its British Virgin Islands division, which was allegedly complicit in tax evasion, though the bank denies this.

Both overseas units have since been closed. But the cases highlight the risks of banking wealth across borders. Banks and regulators are upping their AML and due diligence requirements as a result.

But this also adds costs. Proving an HNWI’s source of wealth is made harder when dealing with clients originating from countries where information is not freely available. A ‘boots on the ground’ due diligence check is very expensive.

Most applicants to Europe’s Citizenship by investment (CBI) or Residency By Investment (RBI) schemes are from Russia, China, Turkey, the Middle East and Central Asian countries, according to a report from the European Commission this year.

“With applicants from abroad, you can’t just check if they’re on the electoral roll. It’s an entirely different onboarding process which is very expensive,” says Farzin.

This process is expected to get harder as regulators ask for more diligence on the source of wealth. “The industry’s increased visibility has attracted a higher level of scrutiny from the media, policy-makers, and the wider public,” Henley & Partners, which offers citizenship and residency planning, said in a statement to PBI.

Despite an estimated €25 billion coming into the EU since 2010 on the back of CBIs and RIBs, according to Henley & Partners, Europe’s policy-makers are already on the case.

In January, the European Commission appointed a “group of experts from Member States”, who, by the end of this year, will develop a “a common set of security checks for investor citizenship schemes, including risk management processes that take into account security, money laundering, tax evasion and corruption,” a statement from the Commission said.

The European Commission is not the only one looking into these schemes. “The OECD’s has been working tirelessly to increase due diligence to avoid money laundering and tax evasion on the GV programmes, which seem to have proliferated in Europe,” says Patricia Casaburi, a director of Global Citizenship Solutions, which advises on CBIs and RBIs.

UK Tier 1 Investor Visa: Successful applicants by country oforigin, 2018

[visualizer id=”83654″]Feeling the pressure, the UK brought forward reforms to its Tier 1 Investor Visa earlier this year. The UK Home Office said it was necessary to “better protect the UK from illegally obtained funds”.

“Applicants will be required to prove that they have had control of the required £2 million for at least two years, rather than 90 days, or provide evidence of the source of those funds,” the UK’s Home Office said in a statement announcing the changes.

“What has changed is they have brought the source of wealth criteria more in line with financial regulations,” says Yazdi.

Though many applauded the reforms for their role in curbing corruption, there is a downside to the increased complexity. While previously many of the major private banks in the UK employed in-house experts to manage the Tier 1 Visa process, few of them do so now.

“A lot of financial institutions have pulled out of this space due to the complexity and risks associated with the investor visa”, says Yazdi.

“Organising and managing an investor visa account rather than an ordinary account – it’s a big difference. You can’t compare the two. Twice a year you have 260 pages of new law. So unless you’re focused on Investor Visas its dangerous.”